Brianna's Jewels

Brianna Jewell

Collection One

In this exhibit, the Grizzly bearnacle was my primary object, and I collected Eyes ex voto and Words and Margins around it. My attachment to the Grizzly bearnacle was strong. Through associative logic and childlike imagining, I was able to both sense and articulate what made the Grizzly bearnacle compelling to me. My relationship to the secondary objects in this collection was deeply influenced by my attraction to the primary object, the Grizzly bearnacle.

Grizzly bearnacle*

The Grizzly bearnacle reminds me of Allyson Mitchell‘s fuzzy monster creations, and pulls at me similarly. Both take me back to childhood memories and inhabit a space between dream and nightmare. Combining elements of land, sea, and air, the Grizzly bearnacle is big and expansive: I feel like it knows things. It sees, but does not talk. And I do not want it to talk. I want to cling to the Grizzly bearnacle and bury my face in its round tummy. And when I do, I too do not have to articulate a word or express a thought.

Eyes ex voto

These eyes are different from the Grizzly bearnacle‘s. They are hard, wide, and open, and they seem to be gazing into me. They are judging me. But, look again at their wide-openness. Their openness conveys fear and vulnerability. Perhaps, contrary to my initial reading of them, these eyes are not judging me. Maybe, then, I have no need to feel nervous when I look at them. But if these eyes betray more fear than judgment, they scare me anyway. I back away from them like I would back away from a skittish abused dog. I do not trust this species of fright.

Words and Margins

Somewhere between the fear of not reading correctly and the faith that what I need to know will emerge, I read. When I read with eyes ex voto, I read with anxiety. With eyes ex voto, I feel eyes above and behind me. With Grizzly bearnacle eyes, I feel creative and patient. I feel like there is no rush.

Collection Two

In this exhibit, Cards was my primary object. I did not know what drew me to this item. My relationship to Glass helped me to better understand it.

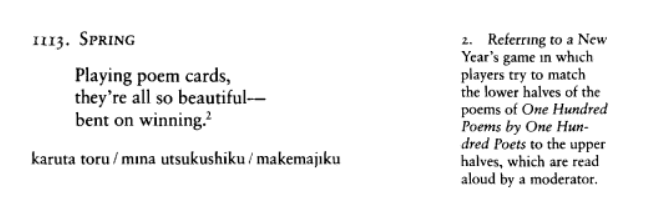

Cards*

playing poem cards

they‘re all so beautiful —

bent on winning.

The first line perplexed me. Each word expressed more meaning individually – playing – poem – cards – than as part of a phrase (playing poem cards). Read together, the first three words conveyed less a defined sense than it did produce a feeling or mood — a dreamy, whimsical mood echoed in the second line: they‘re all so beautiful. The third line departed from this building feeling of nonsensical beauty with a deliberate intent: bent on winning. I was eager to understand this shift, and looked to other items in the collection to help me get a grasp on the Cards object.

Glass

Collecting the Glass object around the fragmented poem provoked me to read Cards through the lens of stained glass. Stained glass windows facilitate experiences of beautiful wonder for those who encounter them. Much of this wonder facilitated via stained glass relies on the play of light through a mosaic of variously colored glass, a mosaic crafted through the fusion of different parts. This way of thinking about stained glass helped me read the middle line of the Cards object — they‘re all so beautiful — as a description of what it feels like to behold diverse entities at once (the three words of the first line, for instance). The last line of the poem — bent on winning — still presented for me a deviation from this mood. After the sort of suspension of the middle line, the beholding of wonder or beauty, I read the last line as another way one could deal with the experience of the fusion of the fragmentary: less of a beholding or suspension (where disparate entities can be imagined to coexist) and more as an effort to make sense of, to limit or define — to make less wondrous? — a wondrous thing. In the language of stained glass, this second response (the third line of Cards) would pay more attention to the cames, the dividing lines of stained glass, than it would to halation, the phenomenon whereby light appears to make the lead divisions bleed out and become invisible.

Yet, after reading the note to the last line in Cards, which explains a game of matching the top part of a poem to its bottom half, I reconsider my reading of the poem‘s last line. Perhaps “winning” is not a reductive act, but rather a more open-ended one. Maybe it even reproduces the uncertainty or ambivalence or ambiguity (the suspension that happens through the encounter of wonder). If winning occurs through joining the top and bottom part of a poem, making a poem whole again, it acts as a kind of glue, a fusing thing. Winning, in this reading, inhabits the position of the in-between, and is perhaps in this way more in touch with the wondrous fragmentary than it is with the domestication of it.

Collection Three

The Ring was my primary object in this collection. And because my secondary search yielded objects bearing explicitly on gender and sexuality, it helped me understand (though I might have on some level already) that my relationship to the Ring had to do with sex. When the Ring was put in conversation with the Dress and the Vulva, though, it made me think about the particular difficulty (or impossibility) of accessing the desire illustrated in the illuminated manuscript (the Ring object). And this made me think, ultimately and through the Vulva, about queer methodology.

*Ring

The ring in the image is big and looks like a donut. Because it is so out of scale, it calls attention to itself. The image invites a focus on commitment, the pact that the ring signifies between two people. The curvy lines weaving in and out of the pair are different from the squared lines that enclose them (their frame), and yet I keep trying to read the lines together. This image is hard for me to read. I am afraid of getting it wrong. I do not want to project too much onto it. It feels very important for me to understand this image in context. But why?

Dress

Featuring a decidedly contemporary woman in a premodern dress, this image drips with anachronistic awkwardness. But it also helped me to imagine what my dearest professor asked me to consider when I was struggling with the idea of “touching” the medieval past. He asked me to consider, rather than touch, the act of dressing in temporal drag (Carolyn Dinshaw describes touch as literary method). It was a slippery idea for me to grasp. But this image of a pretty woman, captured in modern technology‘s color photography, wearing the clothing from another time, helped me begin to imagine what it might mean to dress in drag when we are finding points of connection to the medieval past.

Three Phalli Carrying a Vulva

Is the vulva skewered by the marching phalli? This reminds me of the stuffed cunt in a fabliaux that features a knight that makes cunts speak (“Les chevalier qui fist les cons parler”). The cunt, in that fabliaux, was a Sir, one of the guys. Are the phalli parading the vulva around like a queen? And what a lucky vulva, to have three phalli to herself. Can a queer reading of this image allow us to take whatever it contains that is emancipatory, and leave behind the misogynistic and oppressive?

Collection Four

*wall

The wall was my primary object in this collection. I was drawn toward the wall‘s crack. The more I looked at it, the more the crack figured and materialized the simultaneous union and separation necessary for the wall‘s being — the individual bricks, and their joining together. It made me think about how the thing that separates is also the thing that joins and connects, which recalled for me Barthes‘s punctum, that “accident which pricks me” that “sting, speck, cut, little hole.” Like Barthes‘s punctum, the crack in the wall provides a material detail that locates and grounds the generation of connection. The crack shows how disparate bricks unite to form something bigger than their individual parts.

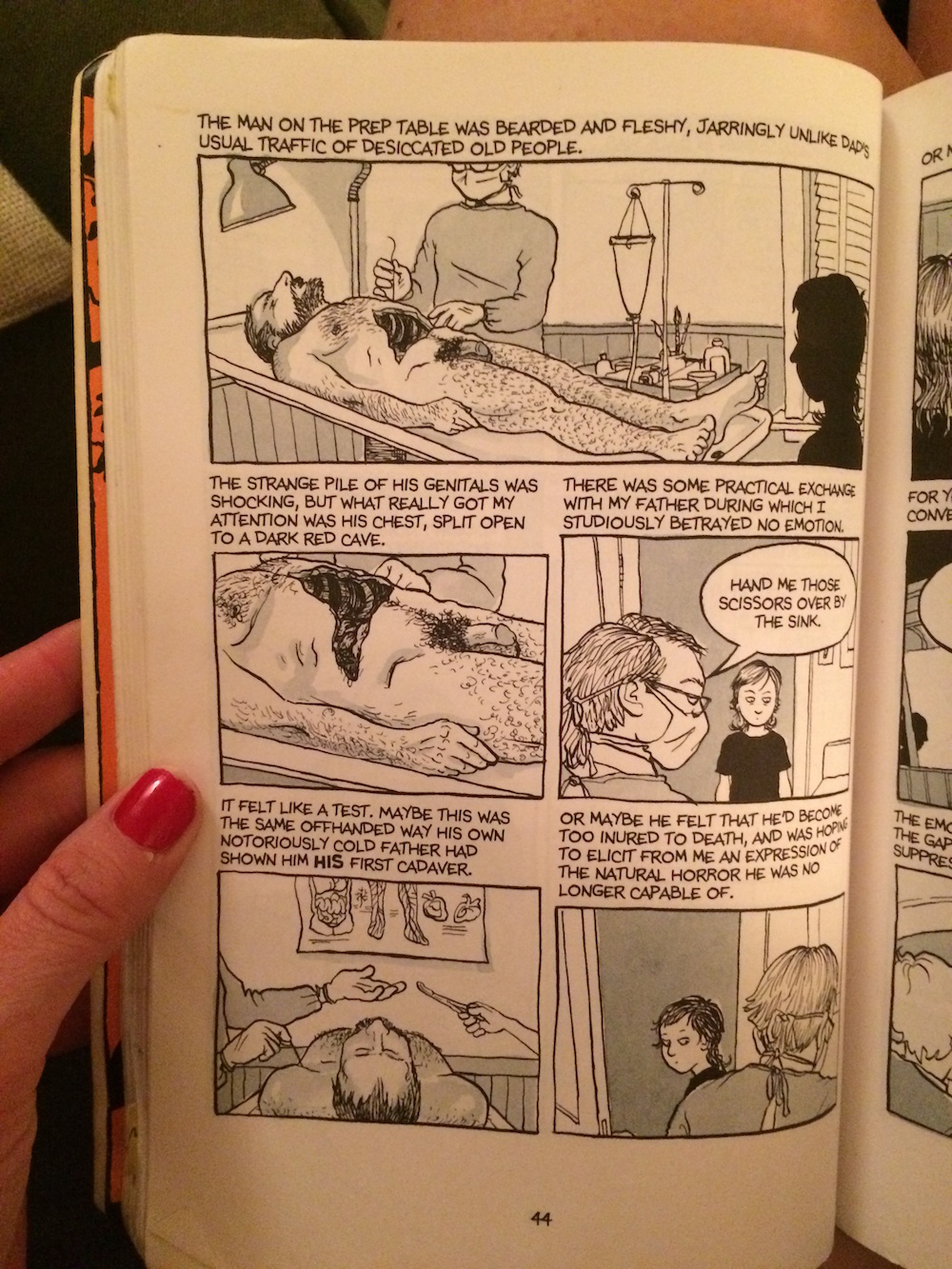

Fun Home‘s cut

Drawing the cadaver‘s cut not once but repetitively and graphically, Alison Bechdel draws us too as readers to the cut. She connects us to the cut as she meditates on the cut as a generating force for connection between her and her dead father.

Broken prayer bowl

Broken apart, the prayer bowl no longer performs its primary function of vibrating meditative sound. But the bowl in pieces — the fragments the bowl becomes — challenge me to think about the metaphors and objects that I rely on to describe affective connection. Eva Hayward writes that “the cut is possibility.” Putting the fragmentary bowl in conversation with the wall‘s crack and Fun Home‘s cut, I wonder if the cut is the primary event necessary for establishing connection — as Barthes‘s theory of the punctum might suggest — or if it is the products produced by the cut that generate affective connection. Is it the smaller fragment, the broken piece of the bowl, that we meditate on — that sense of incompletion, a once-wholeness now lost? Or do we reside in the cut itself when forming connection, as Bechdel imagines?