The Ocean Air

Lara Farina

Inhale (with delight):

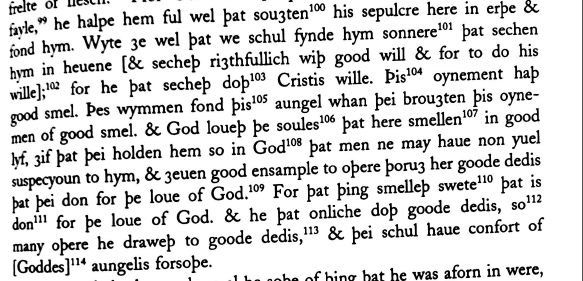

1) Angel Smells

Breath-work is a major component of a number of meditative traditions. I’ve never taken to it that much, but the promise of gustatory breathing is seductive. Our world would surely be better with aromatic angels feeding us their vapors. It must be these spirits who have transformed the footnotes here into little sprinkles of seasoning. Each 100 is like a nubbin of pepper or the clustered black grains of a cardamom seed. After reading that “hope is a sweet spice that stays in the mouth” in an anchoress’s guide to devotion, I was inspired enough to write a thesis on desire. An enthusiastic cook, I really wanted to write about flavor. I just didn’t know how.

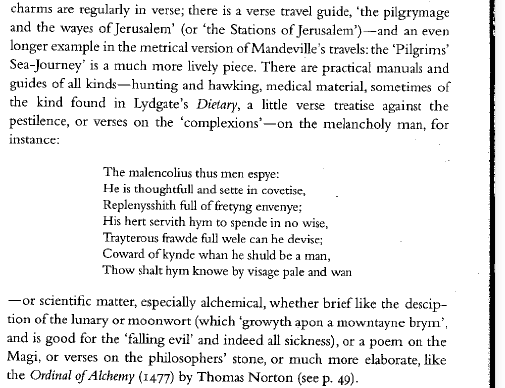

2) Moonwort

Nothing else matters but the moonwort. A plant from the moon! The moon’s special vegetable! The two connect through the deep atmosphere, thickening it with moon tentacles. These pale moon-shoots obscure the word-garden from which this wort grows. I think instead of Max Ernst’s zany sculpture, “Lunar Asparagus,” a tall tube with a scuba-mask head, a figure both comic and magic, as though someone put googly-eyes on an ancient rune. Like the loony asparagus, the moon tuber here is best savored by basking in its solitary white rays, or by inhaling its sonic “ooh!” But the vanishing of the moonwort’s textual surroundings gives me pause; perhaps this humorous harvest is not without some harm.

3) Feathers

Not all delight requires the extraction of a singular thing. Taken after I had assembled the first images for The Middle Shore, this photo records a lingering inhalation. I had gone to the beach looking for background images for the website — nothing too busy or striking, some empty sand perhaps. But at the bottom of the dunes, drifts of seagull feathers pooled into downy spreads. In the pictures I took, the feathers lent their airiness to the grasses, twigs, and broken shells they brushed. Too eye-catching for my intended purpose, I tried to use the images anyway, searching for a way to sneak one in. In this, I am like most other scholars. What kind of asceticism leads us to remove the decorative from our creations? It’s as if we begrudge our breath. Plunge into this warm sand; immerse yourself in fluff, straw, tiny skeletons.

4) Skull 2

I worried about how to get a tactile sense of beachcombing into The Middle Shore. But I can at least get a grip on this skull. The curves behind the eyes are perfect handles; the sheen of the material promises a cool solidity. Echoing Lisa Weston, I ask how I would “see” the world if I put this mask on, became a sensory cyborg. Normally, I lose my balance when I close my eyes to focus on the other senses, but this helmet would draw me up with a firm hand, hold me in place as long as I held it. Wearing this mask, I would find my bearings with my skin.

In truth, I don’t know that it is a mask. I don’t know how big it is. I know that it is made of bronze. Yet to me, this skull is a mask the size of my head and hands, snug on my temples and in my palms, and it is made of polished stone. This is not the same “Skull” as the image in Low Tide anyway. Not the same image as the photo I took with my phone camera, or the image in the book that was the subject of the photo, or the photo of the object that was copied for the book. Yet the skull persists in its density, its worn weight.

Exhale (in disappointment):

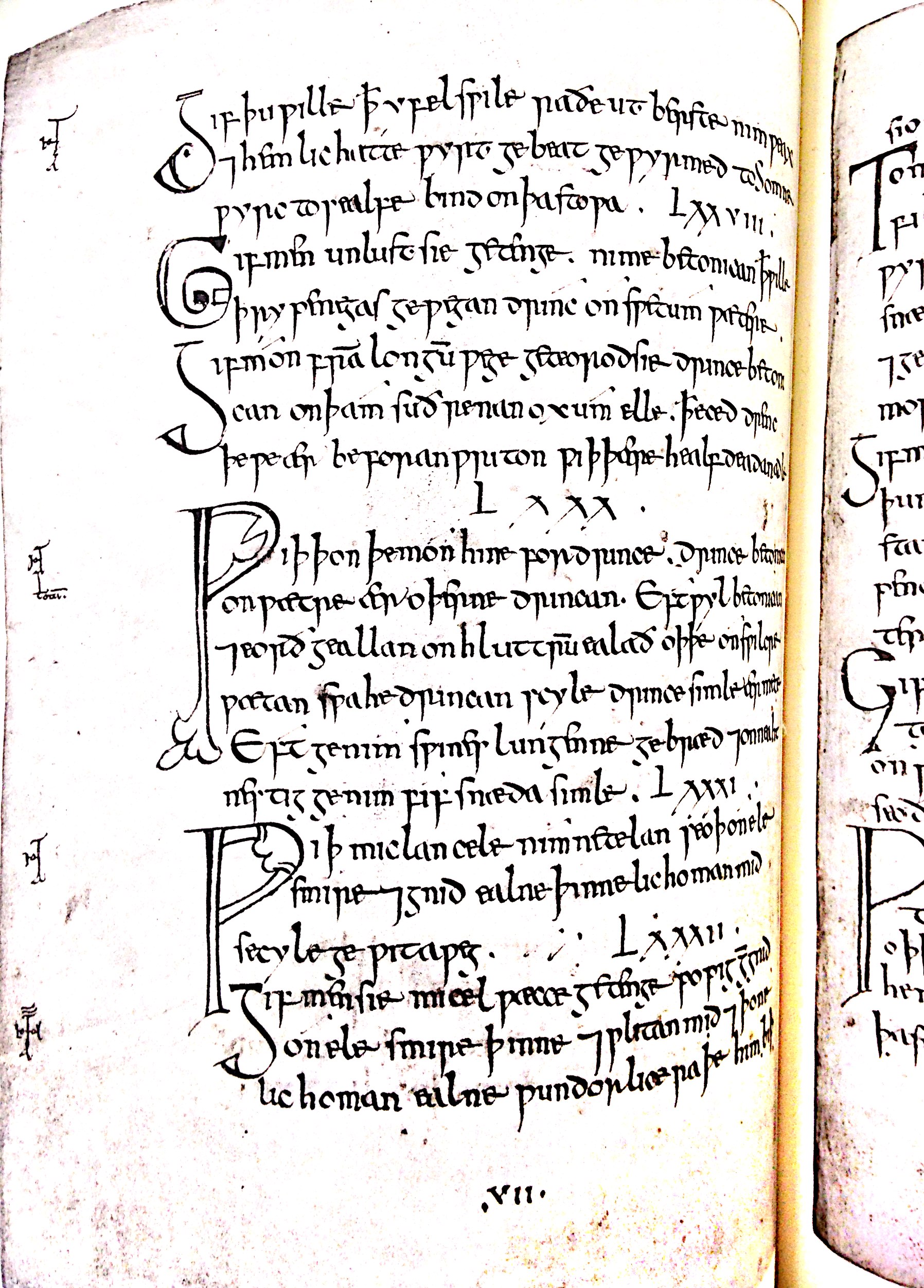

1) Lxxx

Oh, Mr. Bald, Anglo-Saxon monk of herbal majesty, you’ve even risen from the dead to slay the MRSA dragon. Enjoy your 15 seconds of fame amongst the bemused microbiologists and the Buzzfeed journalists. I don’t begrudge you that at all. But as soon as I recognized you in that hefty facsimile that I pulled down, my inhalation started to expire. How had I not visited you before? Who or what brought you to that half-empty shelf of oversized volumes? There you and the other awkward orphans of print are quarantined; forbidden from interfering with the library computer stations, the Starbucks, the study rooms with no books. I am the only one here who might sit down with you now, and I haven’t. I haven’t ordered new books for the library. I haven’t made use enough of the old ones. I haven’t kept up the collection. I haven’t kept up Old English. I haven’t kept up our courses. There is so much to keep up, and I haven’t, I haven’t, I haven’t. Now even your fame can’t bring it all back.

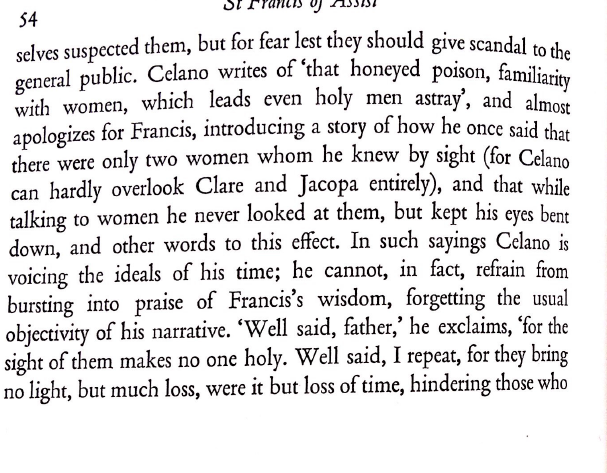

2) Saint

I opened the book and felt myself sink, my shoulders hunching forward, neck shrinking into my chest, air wheezing out. Who put that brick on my head? Who turned me into a shriveled old tire? The man talking about another man talking about another man talking about women, women who shrink into small black holes. There are so many of these men, of course I’d come across some. Duh. I usually try to dodge them or act as if they weren’t there. This time I had to walk into their company. I had vowed to stick with what I found, and, of course, I found a bunch of them, painting Samson, drawing giant wedding rings, clucking in disapproval, winking at each other. I really didn’t want to pass this on to the beachcombers, another Queen of Spades to add to their hands full of heavy hearts. But I didn’t want to be a coward either.

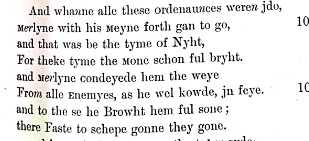

3) Merlin

Strangely, I felt nothing. There’s a big, bright moon, a wizard, and some capitalized, ancient darkness (Nyht!). But the magic didn’t happen, then or now. Perhaps the wonder was squashed by “alle these ordenaunces” pressing downward like a lid made of boredom. Merlin’s magic show doesn’t hide the boring, boring paperwork peeking out behind it. Have you documented the year’s activity adequately? Uploaded each and every email to the appropriate space for review? Completed your workload form, productivity report, tabulation of numbers, review of acronyms, and assessment of your documents of assessment? Even where the pencil-pushing is barely visible, it will still write you into a deep sleep of resignation and defeat. It will make the possible impossible. I never would have predicted that this would be image I withheld from the collection, but it was. I guess it was the document that broke me.

Hold (have you noticed you’re not breathing?)

I’d like to heed Paul Stoller’s call for a “sensuous scholarship,” for scholarly writing that doesn’t ignore the feeling of the writing body (Stoller, 1997). It seems like a good idea, even a necessity.

But my body doesn’t cooperate.

“Wild Man Stoller,” as my seminar students came to call him, has the advantage of being both an anthropologist and a witch doctor. I imagine him putting in the years of squatting on dusty, Saharan earth; smoking thick wads of leaves; listening to the other men talk in low voices; lazily waving away flies; eating magic pastes that taste like dirt and blood. It reminds me of my teenage fantasies of being an ethno-botanist. I wanted to move in exotic zones of visceral difference, to leave American tedium behind, to do a man’s job and have a man’s freedoms at the edge of my culture and my body.

But I am not an ethno-botanist, nor am I an anthropologist witch doctor. And when I write, I am very far from my sensing body. Mostly, when I write, I am solving problems, thinking about concepts, structures, grammars, logics. If I’m moving, it’s through mental mazes, to the extent that I lose track of the light changing, my hunger or thirst, my posture or hands on the keyboard. I tune out sounds, temperature, air currents, odors. Snapping out of it is an effort. In fact, I don’t snap, I slowly resurface. Anyone who interrupts me has to endure my blank stare, my silence, my incomprehension.

I hold my breath, too.

That’s why I need some things that make me breathe.